Kodachrome

|

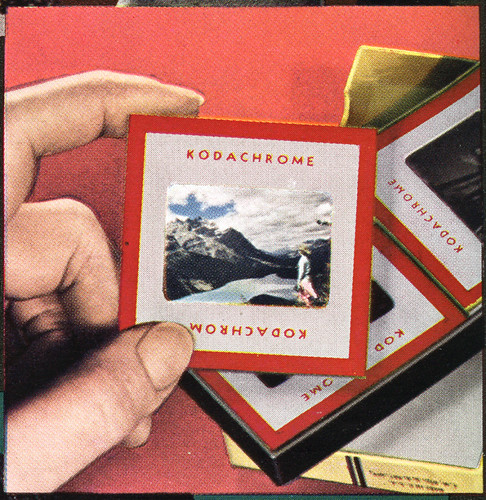

| Detail of Kodachrome slide, from 1945 Kodak advertisement image by Voxphoto (Image rights) |

Kodachrome was the trademark used by Kodak for a series of related color films, manufactured beginning in 1935 and ending in 2009.

Contents

History

Color photography began in the late 19th century, with systems requiring three exposures with color-separation filters. In the early 20th century, the Autochrome process by Lumière used plates which incorporated a random pattern of starch grains dyed in these different colors. Of the processes developed in the 1930s which replaced Autochrome, Kodachrome was the most successful.[1]

Kodak began researching color imaging in its laboratories as early as 1910, and experimented with a number of color processes; but none had proved fully satisfactory (although one primitive two-color process did give rise to the first use of the name "Kodachrome").

Finally in 1930, Eastman Kodak Research Laboratory director C.E.K. Mees was persuaded to support the research of Leopold Godowsky, Jr. and Leopold Mannes, two young photography enthusiasts whose drive to improve color photography had derailed their careers as professional musicians. After solving a number of technical problems, "God & Man" perfected a multilayer color film and a developing process that infused appropriately-colored dyes into each layer during development. This aspect of Kodachrome remained consistent through its entire history, and means that a Kodachrome slide will have its image visible in slight relief on the emulsion side.

The new Kodachrome film reached the market in April 1935, in the form of a 16mm movie film. Because the film was meant for projection, the process was designed to yield a positive image, rather than the negatives typical of black & white films. Kodachrome movie film soon became available in 35mm width; then in 1936, the 35mm film was made available for still cameras too. It was an early use of Kodak's brand-new metal disposable 135 cartridge, introduced for its high-end Kodak Retina camera.

The need for fine grain when when projecting small frames, and the loss of sensitivity caused by the color-filter interlayers, meant that early Kodachrome had a particularly slow film speed—approximately ISO 10.[2]

Over the decades of its production, the Kodachrome emulsion evolved several times. In its peak years Kodachrome could be bought in versions of ISO 25, 64, and 200. However in its final three years, the ISO 64 version was the only one still in production. The development process too had been refined through several versions, with the last one designated K-14.

Kodachrome characteristics

Kodachrome was appreciated by photographers for its vivid but natural colors. It had a fairly contrasty nature, which meant that exposures needed to be very accurate—however, this lent the resulting slide a pleasing "snap" when projected. Kodachrome was much loved by travel and nature photographers (the pages of National Geographic magazine were full of it). Ultimately Kodak was outflanked for these uses by new film emulsions such as Fujichrome Velvia, which offered highly saturated colors using the simpler E-6 development process.

Kodachrome is especially prized for the archival stability of its dyes. When stored in the dark, colors remain intact and vivid for decades, so many Kodachromes from the WWII era look barely faded today.

Historical significance

|

| 828 Type A film, dated 1952 image by Geoff Harrisson (Image rights) |

For a great part of its history, Kodachrome was not available in roll film sizes such as 120 and 127. Professional users could obtain Kodachrome as a sheet film; but for most amateurs, shooting Kodachrome meant shooting 35mm only (or Kodak's 828, unperforated 35mm on a paper backing). This helped push 35mm photography to increasing popularity, despite early dismissals of such "miniature cameras." Without the lure of Kodachrome, it is not clear that the affordable 35mm Argus A would have achieved its great sales success, and this could be said of many other early 35mm cameras.

The prevalence of Kodachrome slides also spawned a secondary market in slide projectors, and the tradition of the home "slide show"—a metaphor that survives in computer software, even as photographic slides on real film have become a rare curiosity.

Kodachrome images are deeply intertwined with the visual heritage of our world—from Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay's ascent of Mount Everest to the Zapruder film of John F. Kennedy's assassination.

The end of Kodachrome

The K-14 development process is a complex one, requiring 14 steps,[3] each of which has to be calibrated very accurately. By the mid-2000s, sales of all film had declined steeply; and in particular, the volume of Kodachrome exposed had dropped to a level where one single development lab could meet the entire world's demand. Thus Kodak closed its last K-14 lab (in Switzerland), and contracted with Dwayne's photo in Parsons, Kansas, USA to serve as the final Kodak-supported K-14 lab in existence.

|

| The final version of Kodachrome, packaged in 135 format image by Carlos Santisteban (Image rights) |

Kodak announced in June 2009 that sales were not sufficient to keep the complex film in production any longer.[4] Learning of this, veteran National Geographic photographer Steve McCurry made a special request of Kodak to receive the final Kodachrome box to come off Kodak's packaging line. Carrying this 36-exposure roll halfway around the world, he began shooting it in India, stopped in New York, and finally exposed the final few frames in Parsons, Kansas before hand-delivering his roll to Dwayne's. A selection of those images was posted on his blog.

However this was not the "last" roll of Kodachrome for Dwayne's. Having promised they would continue K-14 service until December 30th, 2010, in the final days they were flooded with film rolls, as photographers everywhere unearthed Kodachrome from closets and fridges for one last nostalgia lap with the venerable film. It took Dwayne's until January 18, 2011 to clear the backlog of Kodachrome orders. As planned, the final roll put through the processor was one shot by owner Dwayne Steinle himself; its final frame was an image of the Dwayne's staff posing in commemorative Kodak-yellow T-shirts.

Notes and references

|

| image by Raphael Borges (Image rights) |

- ↑ Autochrome Lumière on the Wikipedia.

- ↑ In the 1930s, several competing measures of film sensitivity were in use, and the ASA standard did not yet exist.

- ↑ Angela's Post: Kodachrome Part 3: Meet Dwayne's Photo (archived) at the Smithsonian Studio Arts Blog

- ↑ Kodak announcement of Kodachrome 64 discontinuation (archived)

Links

- Kodachrome at Wikipedia

- A short technical overview of Kodachrome (16mm movie film) from the Kodak Research Laboratories, credited to Mannes & Godowsky, in The New Photo Miniature No. 4 (September 1935) pgs. 222-223.

- "Eastman Kodak Introduces Full Color Photography" by David Lindsay at PBS The American Experience

- "Kodachrome 2010" (9:37), a film by Xander Robin on Vimeo; includes comments by Grant Steinle of Dwayne's Photo on the K-14 process, and glimpses of the processing line in operation.